Reflections on my first Kaggle Collaboration

An exploration of working with a friend to dive into machine learning.

Transitioning from coursework to practical application is difficult. It’s one thing to take courses on Data Analysis for Social Science or Probability - The Science of Uncertainty and Data. They provide a solid foundation and theoretical framework to work with. It’s another to apply that and achieve results. I struggled a lot with finding ways to make use of what I’m learning because my previous jobs have been in SEO (Search Engine Optimization) and did not afford me the time or freedom to do it through my work. In November of 2021 I reached out to a friend of mine to see if he had any interest in exploring machine learning. To my great joy it turned out he did and we agreed to team up and try to do some Kaggle competitions together.

We decided to tackle the Natural Language Processing with Disaster Tweets as a good entry point into the world of Kaggle Competitions. The rest of this post describes our process and my personal learnings.

Note: I am focusing on NLP (Natural Language Processing) because there are many ways I can incorporate it into my work, which will only serve to reinforce everything I’m learning along the way.

Setting goals

I find a good place to start any project is with concrete goals and how to work together. It comes from years managing projects across organizations and clients where success depends on how well you understand the end state at the front. We took time in our first meeting to set the groundwork, below are the list of the goals we came up with.

The goals of our first project:

- Test Kaggle Notebooks to see how they work and the odd nuances that come with a specific product

- Classify tweets as 1 (pertaining to a disaster) or 0 (not pertaining to a disaster)

- Get comfortable working as a team

- Get a better sense of using NLP for text classification

Developing a process that works for collaborating

While we had explicit goals, we did not have any process for achieving them. We’re two friends after all and so we just decided to wing it. That worked surprisingly well, all things considered. I did a lot of research and exploration and then we worked together to refine things as we ran into problems.

Merging teams and then code

Kaggle has some really excellent tools that you get access to for free. Each person having the ability to work in a notebook with access to GPUs is excellent. We initially started our work separately, and then about two weeks into the process we decided to merge our work and create a team. The creating a team part was simple and seamless. The merging of code was completely manual. I can’t blame Kaggle for that, they give you a bunch of stuff for free. It’s just one of those aspects of the learning curve that I feel is unavoidable. If I were to do it again I would say:

- Do not start your project in separate notebooks on Kaggle unless you plan to merge very early

- Make sure the person who has more detailed code becomes team lead

- Copy your notebook locally before merging teams so that you can merge code later with ease

Once the team was formed we had to figure out how we were going to do all of our future development. This lead to some interesting discoveries about versioning on Kaggle.

Developing in Github vs Kaggle

Once we had built a team we both tried to go into the notebook and start to work synchronously. First, there’s no functionality to allow for simultaneous editing (not a big deal as it’s all free) and no concept of branches or pull requests that I could find. This became much more problematic as we realized that Kaggle doesn’t always default you to the last edited version, but rather the last version you touched. When you want to go to an updated version you have to “revert” to it, which doesn’t really make sense if you’re on v8 and the latest is v14. This through me for a loop more than once.

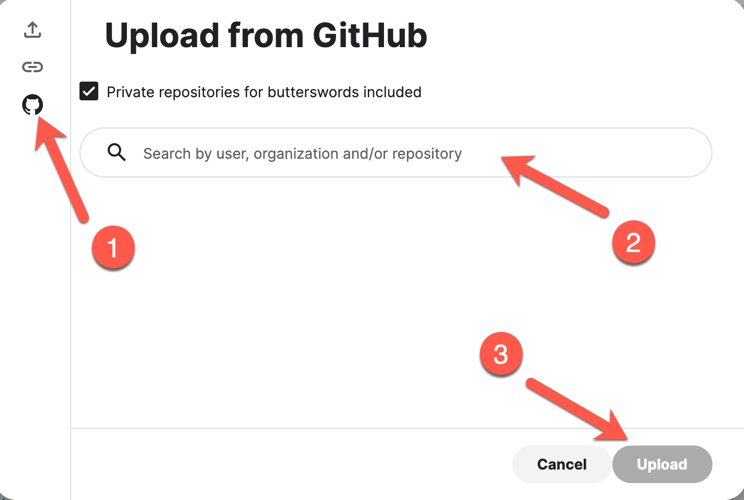

A saving grace, at least for me, was that Kaggle allows you to import notebooks directly from Github. That allowed me to download the latest version and then work locally (like a branch native to Github) and then I would pull from Github when I was ready to push it back into the Kaggle environment. The functionality for that is very basic, however, which made for some interesting renaming of repositories.

- There’s a quickselect for Github, which is nice.

- The search functionality is powerful, but flawed. There should be an option to select only from private repositories connected to your account, not just an inclusion of those in your search results.

- The upload is nearly instantaneous depending on size of the file and your internet speed

It was much easier for me to develop in Github than directly in Kaggle because I could use my Jupyter Lab settings and keep files locally. One caveat, you have to maintain a line of code for loading data in each cell that allows you to switch between environments. I would likely consider adding a helper class for much larger projects that detects the environment and automatically updates the path for reading files. Though manually switching, see below, isn’t too problematic if you have limited inputs.

'''In this scenario I am editing my notebook on my local machine.

So I have commented out the kaggle-specific pathing.'''

#sample = pd.read_csv("/kaggle/input/nlp-getting-started/sample_submission.csv")

sample = pd.read_csv("sample_submission.csv") # For Local machine

At the end of the day, I think it makes a lot more sense to develop non-GPU code in Github. You can then import the notebook into Kaggle to train the models.

note: I have not tried this for GPU-specific projects, like deeplearning for NLP or Computer Vision yet. I may update this line based on my experience when I get there.

Developing different methodologies based on different tutorials

Developing asynchronously, we each took a different way to exploring approaches to the problem. We found different Kaggle Tutorials and that led to some very interesting early discoveries. We realized that there were so many ways to approach the problem that it made sense to test our work against each other and see if and how we could improve on one another’s work.

My friend used an NLP Getting Started Tutorial that is widely viewed and used (roughly 100K views and 2.3K copies). It achieves a base accuracy of around 78%.

I took the approach of incorporating some of the work I was doing through codecademy’s Data Science Career Path with SKLearn’s tutorial on NLP: Working With Text Data. This lead me down several deep rabbit holes, but was richly rewarding for a better understanding of creating pipelines with sklearn, more on that later. My final model achieved an accuracy of 82.08%, which is not an insignificant improvement over the original. Though admittedly it was more complicated and less efficient.

Below is a simple look at all the libraries we ended up including based on our work together.

#Import all major libraries we'll need to create and run our models

import numpy as np # linear algebra

import pandas as pd # data processing, CSV file I/O (e.g. pd.read_csv)

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split #Standard for building Training and Test sets in data

from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler # To process what we need

from sklearn.model_selection import GridSearchCV #To optimize our model's parameters

from sklearn.pipeline import make_pipeline #To make a pipeline for GridSearchCV

from sklearn.feature_extraction.text import TfidfVectorizer, CountVectorizer #Two of our text processing pipelines

from sklearn.svm import LinearSVC, SVC #Loading a Support Vector algorithm to classify the text

from sklearn.linear_model import RidgeCV, LogisticRegression #for StackingRegressor

from sklearn.naive_bayes import MultinomialNB #Loading a Bayesian algorithm to see if it's more accurate

from sklearn.metrics import confusion_matrix, ConfusionMatrixDisplay #For Identifying the type of errors

from sklearn.ensemble import StackingClassifier, RandomForestClassifier #for attempting to combine multiple models

Testing methodologies, comparing results, and choosing a model to submit

Because we took different approaches we wanted to formalize how we evaluated and compared our models to see what we were going to submit. This was mainly for ease of our communication as Kaggle allowed us to submit 5 times a day, and we could do it for as long as we like. We ended up using simple line of code recommended in the documentation and almost every tutorial to evaluate accuracy.

print(f"Accuracy: {svc2.score(X_test, y_test) * 100:.3f}%")

It worked well to gauge between models on the test data. Where it was really informative was in showing us how the performance on test data compared to the competition data. I want to take a moment to note that I use test here because it is the language used in sklearn.model_selection.train_test_split and it is better to consider our test data the validation data based on my understanding from the FastAI course.

Key learnings from the experience

I learned a lot in tackling that first competition. Some of it was mundane (Ex. how to set up environments and move between them) while others were truly enlightening. The ones I will carry with me and want to share are outlined below.

Collaboration

Working in the same file can be laborious without clear boundaries

As I’ve mentioned previously, Kaggle’s inability to provide branches makes it rather difficult to work on different methods in the same workbook. In addition, having multiple models and preprocessing gets to be a terrifying prospect as your notebook grows and grows alongside your experiments. I ended up commenting out all of my friend’s work in the end so that I could make sure I didn’t accidentally overwrite any of my own or refer to a dependency in the wrong form.

- Communicate clearly what libraries you intend to use

- Have standardized naming conventions

- Make sure you use unique names for models, data sets, training sets, etc. so that you don’t run into broken dependencies

A system’s ability to do simultaneous version control is an active constraint for group work

I’m not a developer and so I haven’t used Github extensively. I’ve had an account on and off for years, hoping to dive deeper but without collaboration it just didn’t seem to matter. This project opened my eyes to the criticality of version control, branches, and pull requests. I strongly recommend that any collaborative development be done in an environment that allows for those three things (at the least) to ensure you don’t break everything.

Data Science

Experimentation with preprocessing leads to insights about the data

Throughout the work I tried various ways of preprocessing the data to make it fit different models in the documentation. I lokoed across multiple sources and pieced them together to create a few things that were novel to me. Below is one example. I wanted to see if adding in indicator variables for missing data could improve the performance of my models. It didn’t, but it lead to me figuring out how to do some very basic data augmentation, something I know I’ll be exploring more as I continue to learn.

#Here we'll fill Keywords and Location with "Not Available" to see if this can improve our model. We'll also add indicator columns for missing data to see if that's important.

def add_indicator(col):

def wrapper(df):

return df[col].isna().astype(int)

return wrapper

training_clean = training.assign(kw_miss=add_indicator("keyword"))

training_clean = training_clean.assign(loc_miss=add_indicator("location"))

training_clean = training_clean.fillna("Not Available")

training_clean = training_clean.drop(columns="target")

Experimentation from documentation produces limited performance increases

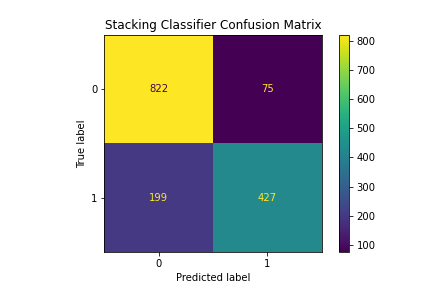

Following some exploration of different architectures within the sklearn documentation I ended up submitting a StackingClassifier to the competition and achieved 82.01% accuracy. This was a marginal improvement over our previous attempts that ranged from 80% to 81.4%. However, the really cool thing I found in doing it was learning more about how to create pipelines that allow for combining different methods of classification to increase performance. I had one pipeline that used a CountVectorizer to preprocess the training data for RandomForestClassifier and SVC classifiers. I also used a TfidfVectorizer that preprocessed the data for MultinomialNB and LogisticGregression classifiers. This allowed me to combine four separate estimators before learning the final classifier on another SVC. While this is an inefficient way to train models, especially as it did not provide significant performance. I found it to be a great opportunity to explore different workflows.

Below is a picture of the Confusion Matrix for the final StackingClassifier that highlights how it performed. Doing this over again I would look deeper into what was causing the false negatives to see if I needed to do data augmentation or select better hyperparameters to improve the model by a larger margin.

My biggest takeaway regarding Data Science is that experimentation and adjusting hyperparameters are critical parts of developing an accurate model. It feels a bit like trial and error, relying heavily on intuition, and you have to understand how they affect the underlying architecture, individually and in aggregate, to make the most of them. This is part of why I am working my way through the FastAI Course. I want to develop better intuitions and a deeper understanding of the theory underpinning the architectures so I can make better choices.